In another of our monthly Google Hangouts with experienced and talented audio engineers Brad Pierce, Joseph Baffy and Joshua Wilson, we continued in our efforts to bridge the gap between what you are hearing as an engineer and how the room is causing that problem. The following video and transcript comes from one particular section where we addressed the issue “How To Record Drums In The Studio”. If you would like to see the full hour and a half discussion you can see the video further down the page.

AD: The point of this week we are going to dive into the world of recording drums. It’s a problem area for some people so we want to pick your brains on how you guys have done this in the past. Successes, failures, learnings, etc. We’re going to start with you guys as engineers and then later get Dennis’ input as far as room acoustics… ideal dimensions, drum rises, that kind of thing.

So Brad I guess to start off then, Brad and Joseph, when you guys are recording drums, do you just want to talk people through some of the processes that you use when setting up to record drums. What’s the starting point that you want to recommend?

Brad Pierce: Joseph, do you want to chime in here?

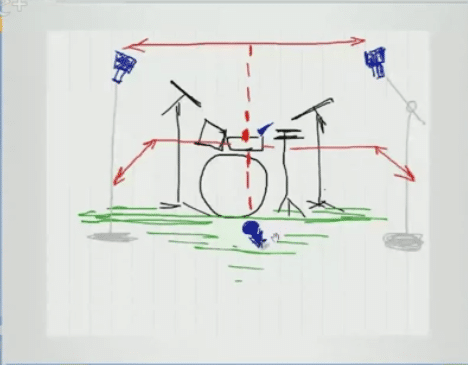

Joseph Baffy: Certainly, I’m going to do a quick screen share if that’s okay? And I’m going to show you a picture rather than trying to describe it.

The blue blotches represent microphones and the stick figures are drums and the red lines refer to their proportional positioning where you’re going to put your drums. And this is one of my favorite set ups right here.

I start with the overheads first and I generally like a cardioid pattern condenser. I’m not that picky. The NT-1A is just fine with me although I do like some other mics as well though. And I really work hard positioning those overheads, equal distance from the snare, where the red lines are kind of indicating. The center line of that snare both in the vertical and horizontal position I want to get those two overheads as close to the money as I can. And I listen to those, and I want those to capture the meat and potatoes of the drums. I mean I really want to hear basically the whole kit and have it sound like I’m in the room when it’s coming out of my speakers minus maybe a bit of that punch that you’re going to get from that next two mics.

The blue bob in front of the kick, that’s going to be about 12 inches away, a little bit off center kind of where I have it shown as the snare, in center with the snare. That equates to sometimes approximately 5 inches off the center. It may be 5 to 7 inches off the center of the actual kick drum and approximately 5 to 7 inches off the floor. Sometimes further, it depends on how the drummer’s playing.

And then the last little blue thing is the mic right on the snare and that’s on the top side and it’s generally pointing at the center or more specifically where the drummer hits his snare. Sometimes they don’t hit the center so if I see the wear pattern, it’s a little off then I point it right at that wear pattern. You know things are subject to change, you know that of course.

This is really, one of my favorite ways to go and I find the better the drummer is, the better this system works for me. The drummer, you know, if he’s playing the drums as an instrument rather than a bunch of separate drums, you know, he plays it as one instrument and it’s played evenly and it’s kind of like a guitar player who can really work the neck, you’ve got to watch what his right hand’s doing cause the way he’s hitting those strings really does a lot with the guitar. It’s an incredible concert between both hands.

And when I find a drummer that really knows his craft I go with the simplest set up I can and I find it works usually the best. It keeps my mics in phase and I get a real nice sound field out of it, a nice stereo field, and with some good accents with the two mics down the middle.

Dennis Foley: Can you comment a little bit about the bass drum. You said positioning is dependent on how the drummer is playing. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Joseph Baffy: Certainly. Sometimes a drummer will show up with his favorite kit and won’t play the studio kit. It might have a hole cut in it. And you know if he’s got a center baffle then that can come into the equation but to be more specific if the drummer is stomping really hard on the kick drum then he’s going to move more air so I have to pull the mic back further.

Brad Pierce: Okay. So it is pressure related?

Joseph Baffy: It is pressure related exactly and it also can change where those overheads go if I have the height I’m going to go up with it generally. It’s going to stay the same distance horizontally and you know in the X, Y but the Z if we call the vertical Z this time then I’m gonna try to get away from the pressure by you know going higher. If I’m stuck in a smaller room then I turn the microphone down.

I turn the gain down tremendously and as long as he’s not blasting the diaphragms with too much pressure then I get away with that. And that is kind of really important thing that gets lost in the background is, depending on the drummer, how they’re playing and Brad even brought this up in his notes, you ask the drummer to play softer and that’s not just the small room recorder, it’s where do you put the microphones when he’s pushing so much air with those drums that your diaphragms, you’re getting distortion through your diaphragm and a more inexperienced guy would think that is having a gain stage problem made. It won’t be gain stage, it’ll be diaphragm distortion.

Brad: Yeah that’s definitely a big factor. Not to take this off topic but just to show Joseph other instances of diaphragm distortion I did a location recording and it had ceiling fans. It was a bit in a big church. They had ceiling fans and it was in June or July so it was very hot in the church. So they had the ceiling fans on high and generally in this room I like to kind of put the mics up you know pretty high. It’s like a huge chorus and they had a huge orchestra, it’s a big place and that one particular time I got diaphragm distortion from the ceiling fans.

The ceiling fans were pushing the air down, the microphones were too close to them, and just that small amount of pressure difference from the fan you could hear it. You know it didn’t completely ruin the recording but you could definitely hear when it was happening so that would be something like with the cymbals. You know if you bring those over heads down too close so you have a small room you want to get maybe a little closer to minimize the effect of the room and he’s beating on those things, you’re gonna have some issues with that. For sure, yes.

Dennis: It’s like a Leslie cabinet for drums? The B3 hammonds with the Leslie cabinets so you’ve got an out of phase horn spinning its same thing with the fan.

Joseph: Yeah I would imagine you’d get some pretty unique sounds with that.

Dennis: Yeah I bet you could if you messed around with it for awhile.

Joseph: Yeah that was one of my favorite things as a kid you know talking to my friends in the fan, in the window. Yeah you know.

Brad: I used to practice piano at home. We had a ceiling fan and I would always have to turn the fan off because the sounds, it would just pulsate and it would drive you insane. So yeah that pressure from non-musical sources as well, for sure.

Joseph: That’s a great example. The first experience I had with pressure was very young and I didn’t even realize it was pressure until retrospect and just give me a minute you’ll see how this will play in. My friend’s brother had a reel to reel two track and he got it in Vietnam and sent it home and his brother, my best buddy Paul and I were recording, trying to record the radio with it.

Using microphones that came with it. We didn’t have a clue what we’re doing and I was already playing acoustic guitar at that time and I had this old stella and I got it for five bucks at a garage sale you know, I mean I loved that thing it was awesome. But I couldn’t get a decent recording no matter what happened. I just couldn’t seem to get anything decent but crappy you know everything we did was crappy.

But you know at least it wasn’t even a good crappy you know and he left the room, it was in the bedroom and he left the door open and I hit record and played cause I didn’t want to get up and shut the door and that was the best recording we made up to that point. And I attributed that to the pressure buildup in that little bedroom. I mean it was a tiny room. To me it was like a sewing room. You know they had four or five boys, one of them was in Nam but you know there were five boys. Four boys living in an average American house it was a little cozy. And that was my first experience and at that time I didn’t know the definition of what that was. I guess you know that we got better recordings when the door was open.

Dennis: You provided a pressure release valve.

Joseph: Yeah, exactly you got it and I’ve used that. That stayed with me and I’ve done the same thing in small rooms recording instruments and have opened the door. Just simply opened up the door and I’ve gotten better results.

Brad: That’s very interesting. A good thing to try next time.

In Summary

To learn more about room acoustics and how drums interact with your room, please sign up to download our free ebooks and video series on room acoustics here. And please let me know if you have any questions at any time.

Thanks

Dennis Foley